Questions for a Sunday.

What is the value in looking back at visual work that you made decades ago? How is it different than, say, looking back at something you wrote in that far away a time? Is there a voice inside my head related to the person that wrote things down that recognizes themselves from then, remembers who they were in that moment? Is the remembering a form of tenderness? Condemnation? Or, as the kids say these days: cringe? Does what we looked at then change what we see now, or is it some kind of Heisenberg principle of uncertainty: the one that looks either then or now can never be objectively taken out of the equation, and so there is no possibility of reconciling the two?

I am looking back through time at work that exists in negatives, zip drives, CDs, some prints. I am avoiding pulling out the film scanner and its attendant outdated daisy-chain cords and adapters, with a punishing 20+ minute scan time for each image. I marvel that waiting that long was ever normal or amenable to my impatient mind, even in 2002. Which in the math of my middle age was just a few years ago, not over twenty. So to avoid the dreaded film scanner I bought a Mac mini with an aged OS installed that could read my iomega zip drive and pull up history through similarly historicized pieces of technology in the form of 3.5” zip drive discs. When 100 MB was the cutting edge of maximum portable hard drive technology, not the size of a single RAW file.

Other anachronisms: this work that I made in the early aughts I was the age of the students that I spend my days teaching now. I was youth. My life stretched out before me, but each day a grind and I remember it did not feel like possibility as much as it felt like pulling through. Why was my horizon line so limited then? In what ways do I do that now? I bemoan my students bounded mindsets when I want them to be excited by ideas, art, their own stories, and they just regard me with their fatigue. But looking at this reminds me of how I think I felt then.

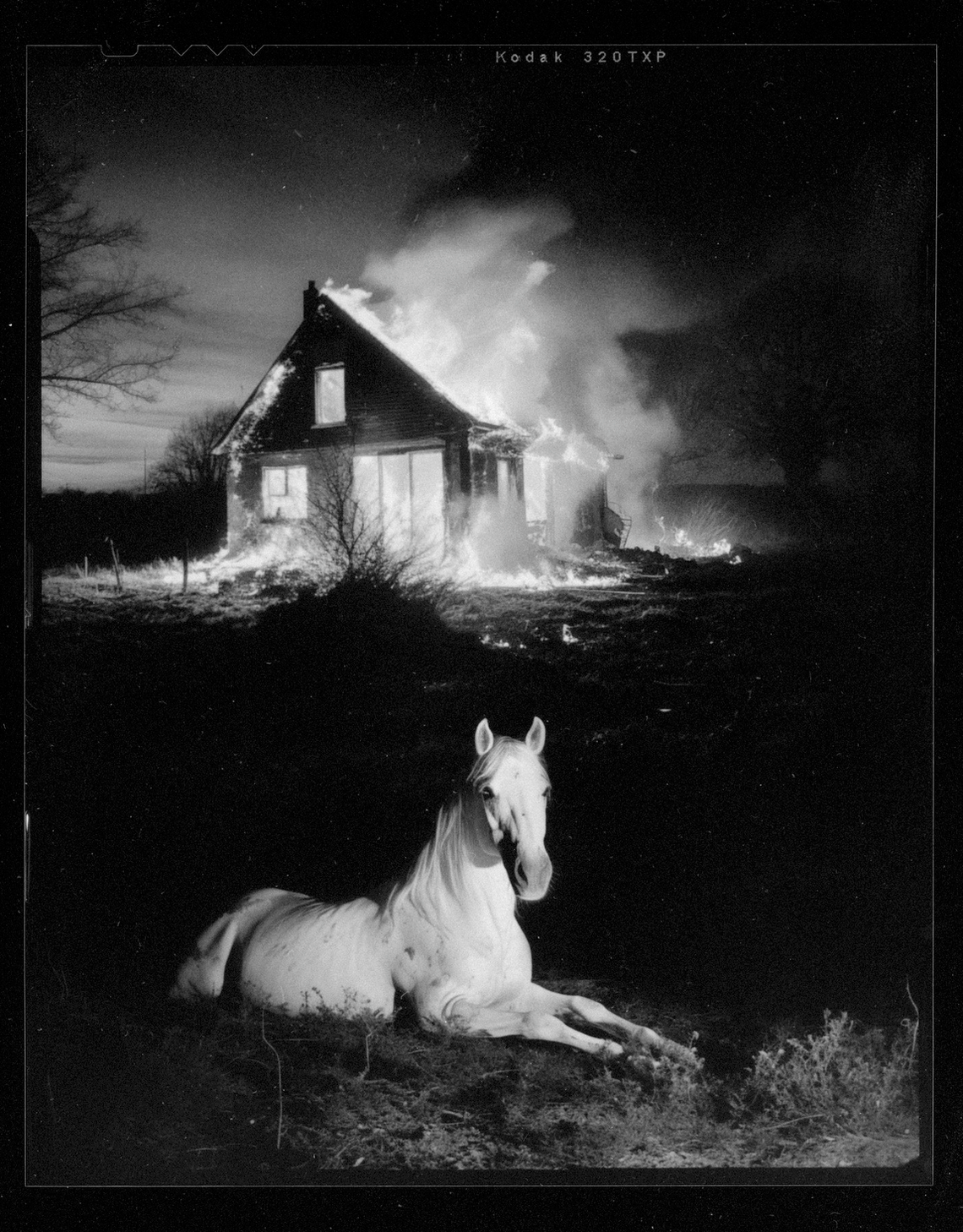

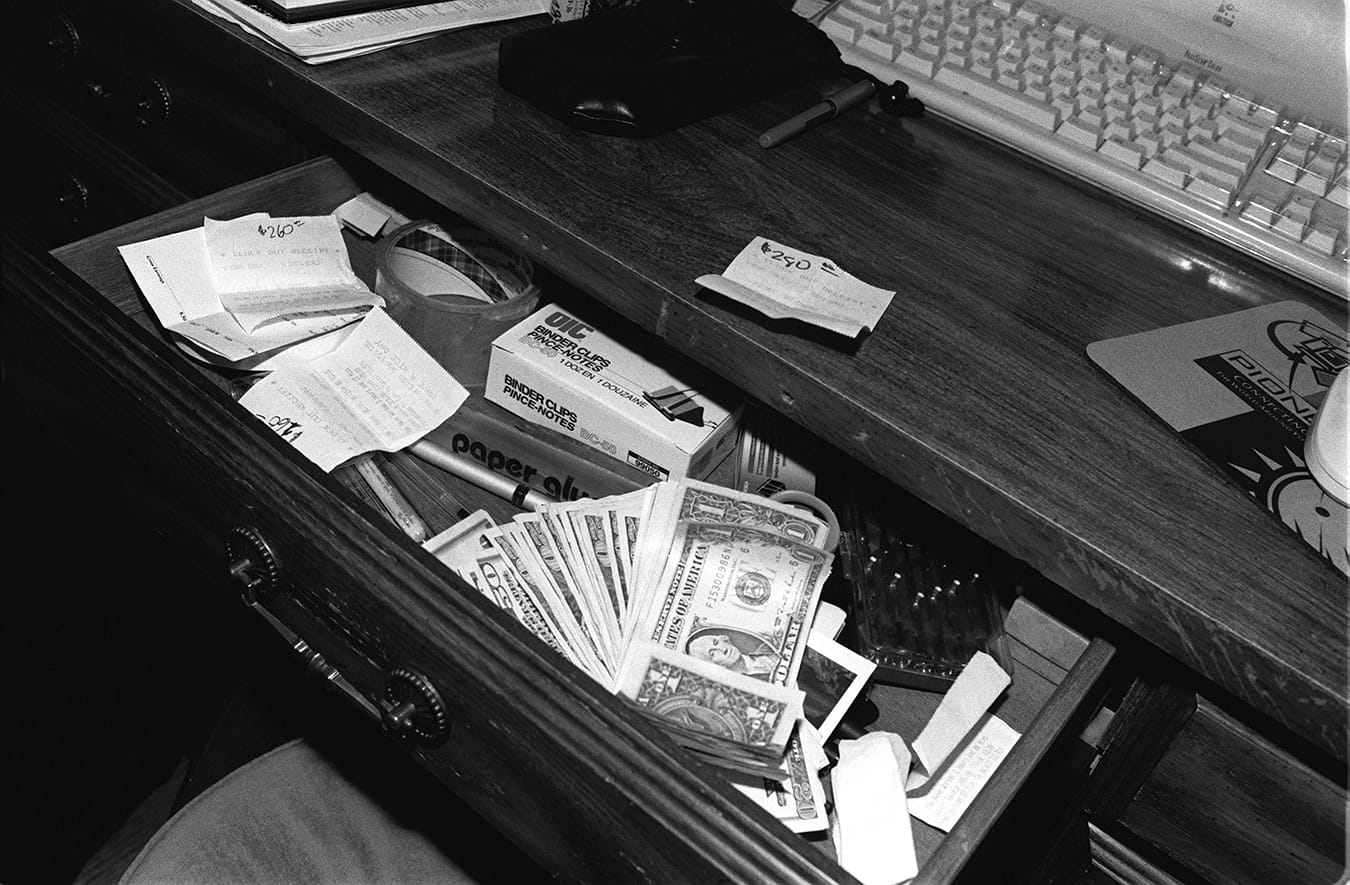

© Stacy J. Platt, (l-r) Done Pretending; Half-way to Rent This Month, 2001.

When I was in the wrong relationship.

When 9/11 happened the second week of my first semester at Columbia.

When I worked at the largest nightclub in the city, and at first it was fun and a spectacle until it was not.

When I couldn’t afford lightboxes, or transparency film, or Cibachrome printing paper, but everyone else in my program could.

When I didn’t have a car, and so the city I knew was only North/South, not East/West because trains didn’t run that way.

When I was very minimally politically aware.

When I didn’t know how to cook anything, and ate mostly staff meals from the kitchens of places I worked.

When life felt very, very contingent, but I was learning that I could always work doing something else if I had to.

When I ran on fumes and drive and necessity.

I still do that last part.

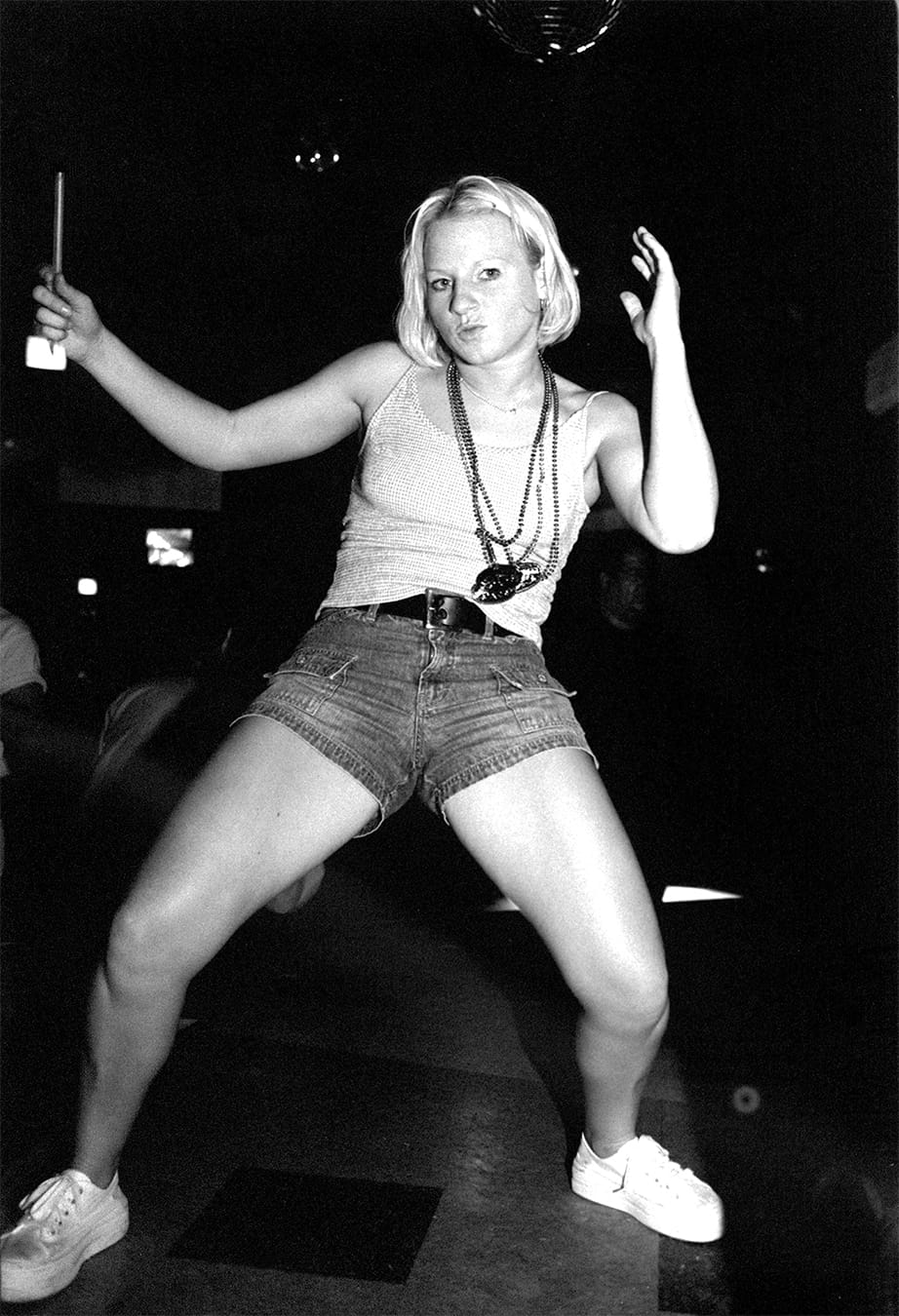

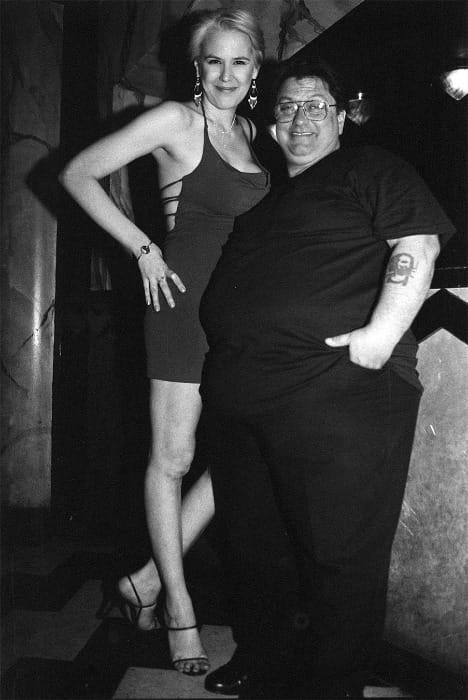

The work I was making then was very exterior to me, even though looking at myself within it was a part of it. I was looking at rather than looking in. Because it was graduate school, I was hyper aware of how it would be viewed by my peers and my professors, and I wanted it to look like All The Things: young, exciting, raw, hard, beautiful and terrible. That list sounds to me like the way that angels were described, but that wasn’t in my head then. The photos were received well—too well, it seemed, and I didn’t trust it. Were my middle-aged white professors getting off on all the scantily clad young women, self included? The images got compared to Sophie Calle, who I didn’t know at the time and then when I did, the comparison pissed me off even more. EWWWW! Calle was rich and bored and enjoyed her own self-absorbed provocativeness far too much for my taste. I was doing this to pay my rent and buy more film for school. I started the project because the entirety of it was accessible to me and was at hand; I knew it was a spectacle and thought that could be interesting. I ended it because I got tired of being looked at like I was in a zoo that I willingly entered, closing the cage door behind me each Saturday night.

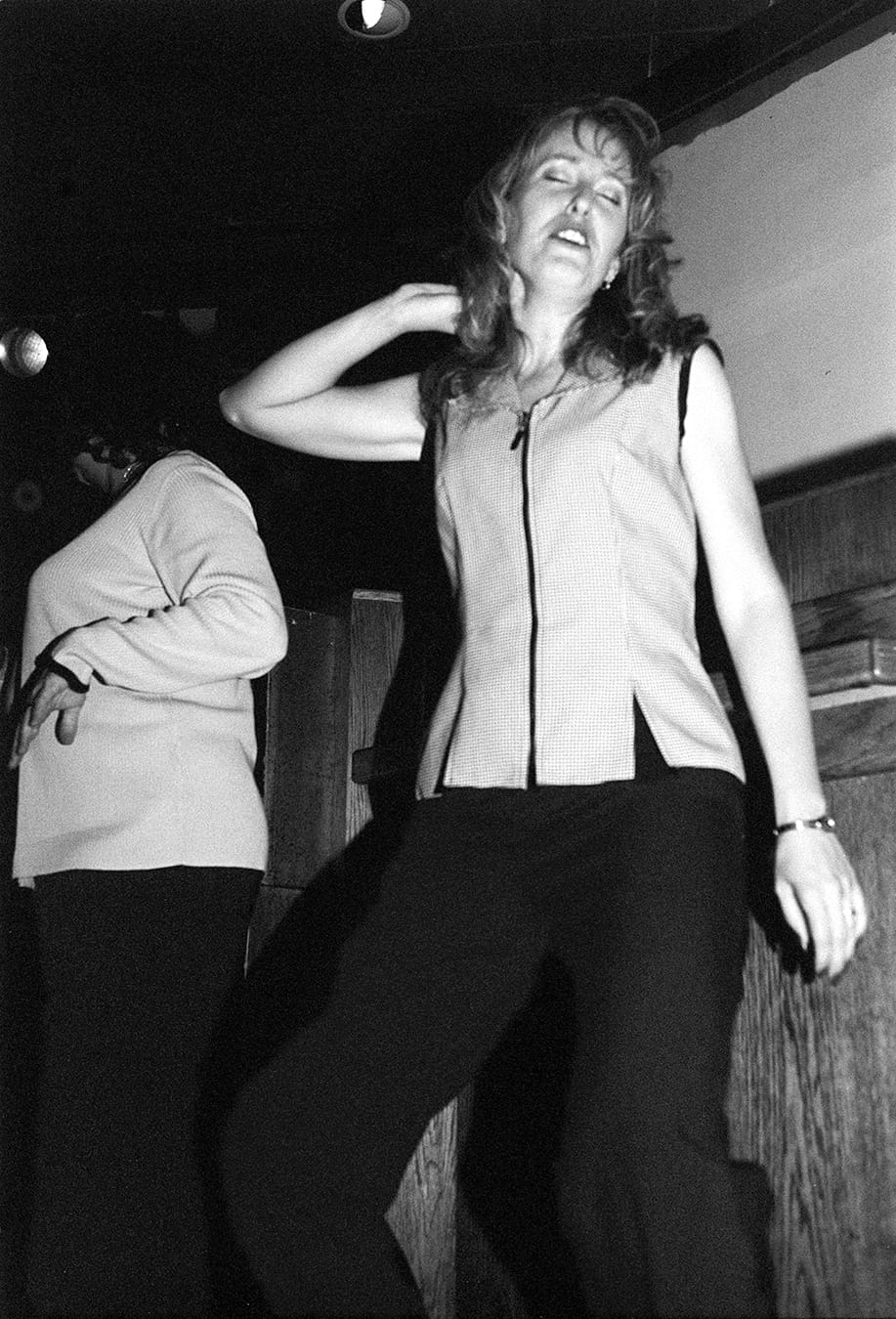

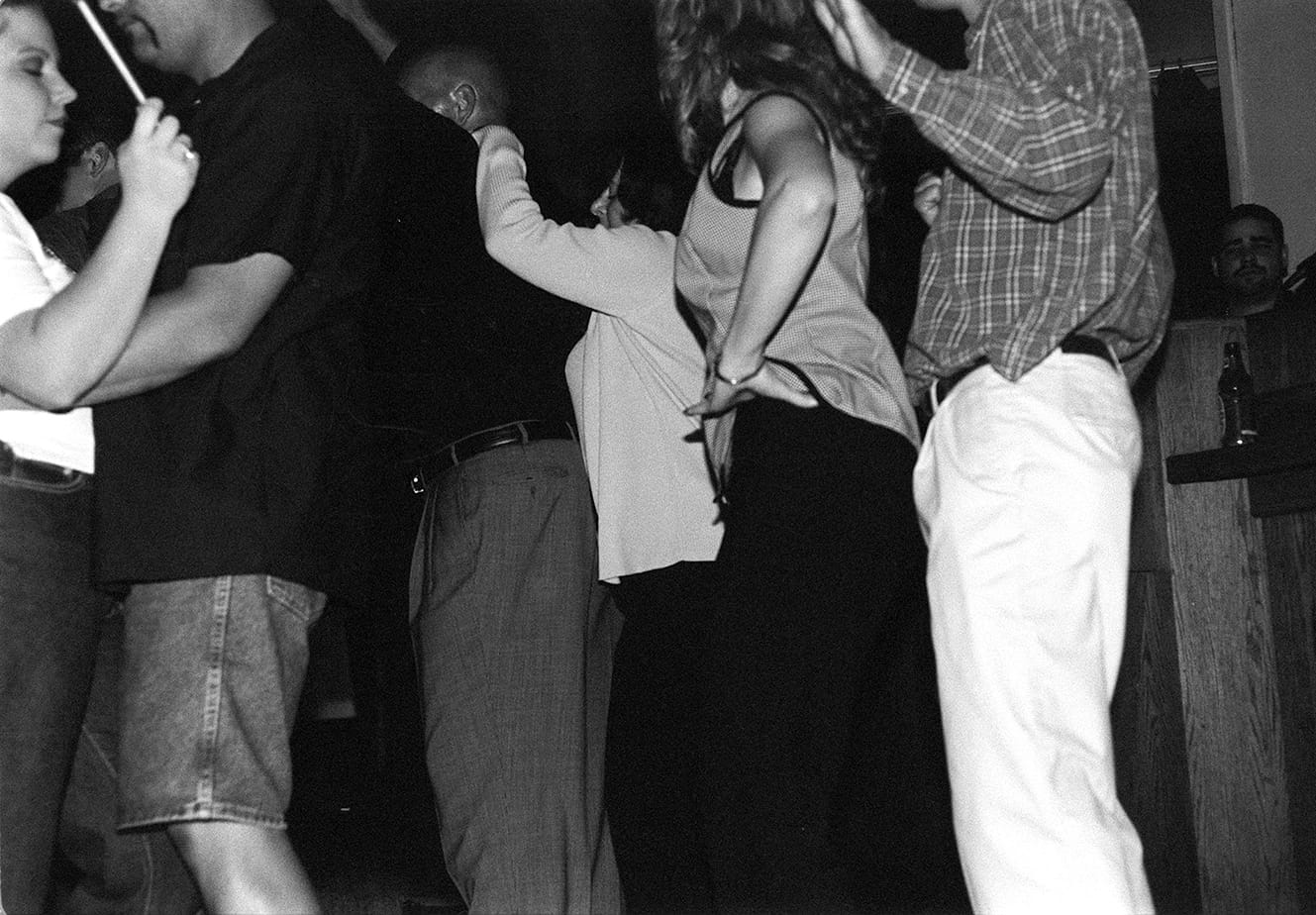

Something that working there then and looking at the photographs now remind me of: this is when I stopped enjoying dancing. Photographing tourists and conventioneers grinding away at each other in their dockers and visible-on-purpose thongs, made dancing look stupid, tasteless and desperate. Nights out that other people enjoyed themselves, spending too much money in a place I spent three weekend nights a week made me never want to spend my own time in such a place. You know when it’s past last call and the lights go on and it’s harsh and everything looks like the reverse of when Dorothy opened the door to Oz? The nightclub looked like that to me at all hours, and I never wanted to feel like that looked. So I stopped dancing. And the idea of dancing ceased to be appealing altogether.

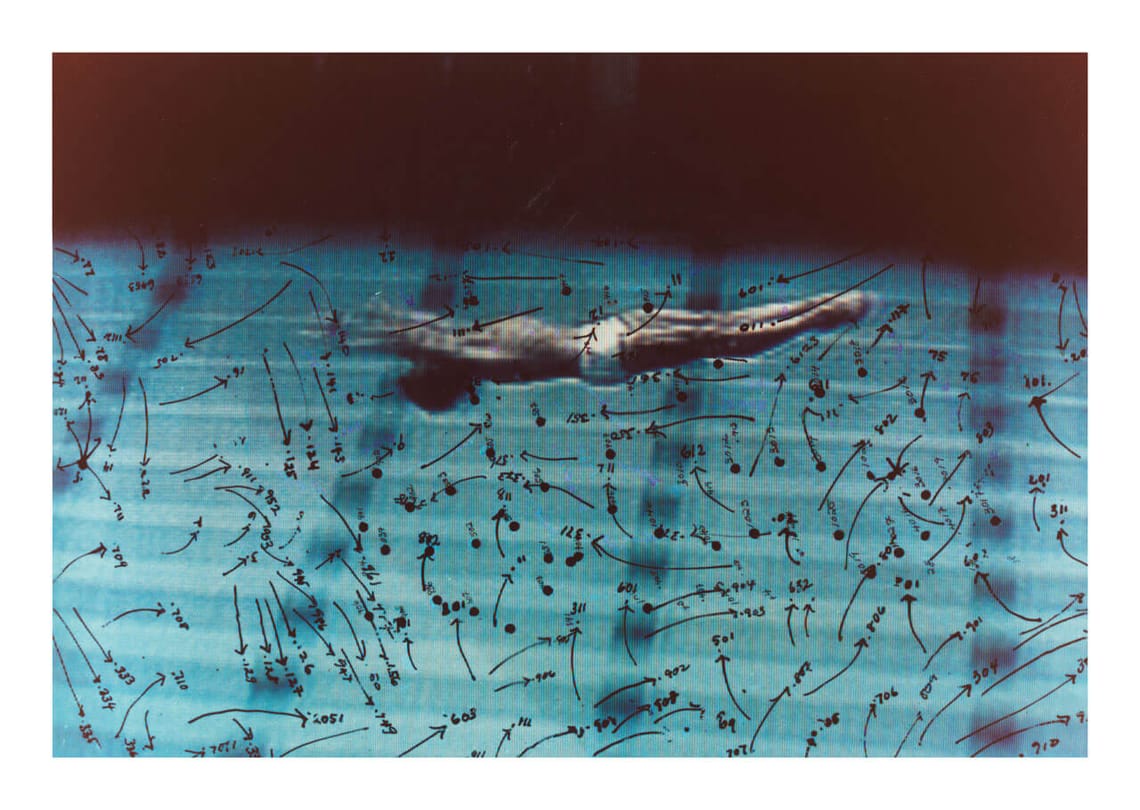

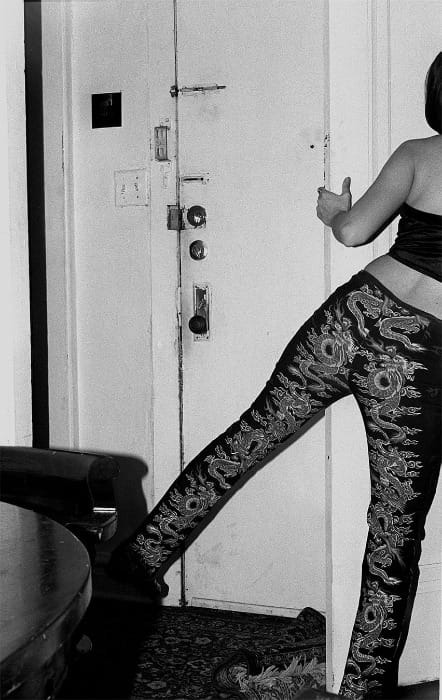

© Stacy J. Platt, Never-Ending-Office-Christmas-Party, pt. I; This Is How You Do It Baby, 2001.

I cannot believe that I ever had a job that started at 11pm and ended at 5am.

I cannot believe that my “uniform” consisted of party-girl clothes at its most come-hither pitch.

I cannot believe my fake name was Veronica; that I had a fake name; that there were good reasons for having a fake name.

I can believe that I’ll never drink shots again.

I can believe why I thought it was a good idea to make a photo project out of it.

I can believe that I was doing the best I could at the time and that that was enough.

And looking at the women and men I worked alongside each week, of course I wonder what ever happened to them. Angel and her sister, who took Amtrak down from where they lived in Michigan each week to work there, because they could earn more over a weekend in Chicago than anything they could make back home, who had five children to feed and clothe and house. What about Mace the bouncer, or Mary Kae the bathroom attendant, or Colleen the waitress that was addicted to cough syrup, and once spent a $21K tip on a muscle car? Did the beer tub girl whose name I can’t remember ever regret getting a boob job for better tips? What ever happened to the shot girl manager, who spent the whole night in a flourcent lit office three floors up from everything, who always reminded me of a madam at a bordello?

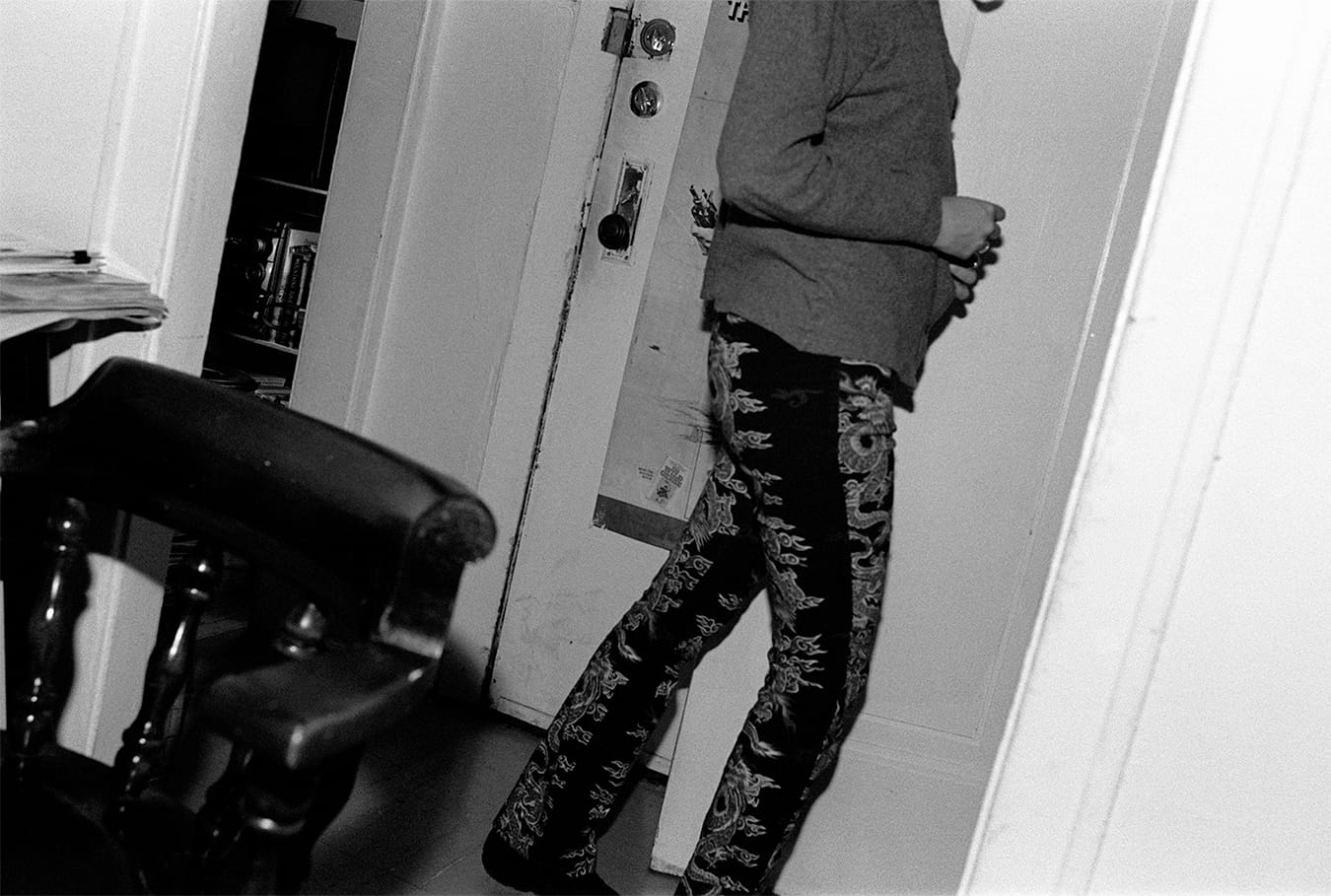

© Stacy J. Platt, Portrait of Mary Kae, attendant at Excalibur Night Club; Angel After The Bachelorette Party, 2001.

Tod Papageorge’s Studio 54 images were part of a lineage that I wasn’t aware of at the time, and later my mentor Paul D’Amato made a book on rave culture that there are also likely parallels to. I love that 1970s image of the woman dancing and her long braid whipping a horizontal line across the frame. Where does this fall within that? Certainly not the glamour, celebrity and over-the-top drug culture of NYC in the 70s (though Prince did frequent Excalibur and no I never got to meet him). These do feel very of-a-place and of-a-moment, though. What is it about that moment these photographs describe?

It is crass consumerism and suburban anxiety and distracted sexuality. It is young women cashing in on their youth and beauty for tips. It is me telling you that shots are $5 each and not the $4 they really are because Midwestern tourists don’t tip, and I need to go home with $300. It is binge drinking and the adult hangover of frat culture that keeps giving into a first big-boy corporate job, vomiting everything out onto the sidewalk in a multicolored puddle with whipped cream on top at 4am. It is regret over what you did with a stripper at the bachelorette party. It is the unscripted, uninteresting set of a dude-bro film shot in the same era. It is wondering if you saw a ghost in that smoke-machine filled corridor because everyone who’s worked there over a year earnestly swears the place is haunted. It is a younger me, trying to make something work in situation and a time when it feels like everything might come together, or it might not. It is negatives and zip drives and CDs sitting in a filing cabinet twenty five years later.

I think the building itself has since become a concept restaurant/shopping center/lifestyle place. It had been so many things prior: a private mansion, the Chicago Historical Society, the Institute of Design, then Excalibur. I wish I had made more photos of it just as a structure. I know I went there once and shot a few rolls to do that. Perhaps I will eventually get that film scanner out.

Can anything look more foreign to your eyes than yourself half of your lifetime ago? Is the disorientation in the looking back at yourself then, or in the knowing who you are now, scarcely able to summon an accurate projection of the person you were? Photography is related to memory, yadda yadda yadda every lazy artist statement ever, but what about when you don’t remember the memory? When it doesn’t look like a life, or your life, but like the set design of a play vaguely recalled? And if you’re an artist, if you’re someone that deals with slices of your life in terms of epochs of thought and becoming, can your youth and what you made while young be anything other than pre-historic? Your buried dinosaur bones and fossils, broken and incomplete and frankly amazing to your eyes after you start needing to wear progressives?

Again: what is the value in looking back at work that you made decades ago? Does this rambling meditation come to any conclusive understanding?

Certainly there’s a rubicon between the me-maker of then and the me-maker of now. There is value in recognizing the feeling and concerns of my younger self, like a perfume on someone passing by me on the street that someone I once cared about wore, and am instantly reminded of. I remember that self and being twenty-four and come back to seeing all of the twenty-four year olds I work with now a little more fully, more sympathetically. But what does it do for MEEEEE? The nonchalance with which I was always thinking about making images can act as a kind of libidinous energy for me now (in the Jungian sense), and maybe I can remember my way back into that youthful energy of making. I don’t what-the-hell it with things as much now as I did then, and it can’t be anything but good to embrace that spirit when I get complacent. While I’ve never liked the perverseness of someone like Winogrand approaching women on the street, I do like the boldness I had in making photographs at Excalibur.

The Cree/Diné artist Kimowan Metchewais contemplated the mature artist meeting his younger self, in a short film made after brain surgery to remove a tumor that left him partially paralyzed. His contemplation of this meeting remains very moving to me:

I'm an older artist, a mature artist, but I have a baby artist in me too. It's weird: I've got two artists in me. I've got this dialogue going: the older artist can kind of help the younger artist, and then the older artist can take the spirit, the energy and the fearlessness and the curiosity of the younger artist, I think. The older artist will know what to cover on the old paintings and the younger artist will be the one that will say, "Oh yeah, go ahead and do that—I don't know that rule that says you can't" and then the older artist will again come back and go: "Wow. That's unexpected. I never thought that would look like that—I never thought that would come out of me." I don't know what's going to happen. When people want to see my new work, they'll say: Oh yeah, Kimowan's new paintings. But damn: they're really good now."

Uncertainty principles not withstanding, I’d like to find some bardo in which the two of me can meet and talk and help one another too. There is value too in seeing the long continuum of making, in photographs and words and in teaching others, as something that ties yourself to your self of your past and who you keep becoming. Longevity of purpose as a virtue.