Whether it's a studio art class, a writing class or a photo history class, I start the first day of every new course each semester the same way: by showing an image that I am near 100% positive my students have never seen before. Before I introduce myself, before I pass out syllabi—before anything—I dim the lights, turn on the video projector, and show an image full screen, no context.

"You are in an art-based course," I tell them. "Might as well look at some art and talk about it."

Students are more than game. This is not how most of their classes start out.

I introduce the concept of Visual Thinking Strategies, which begins with simply asking people to describe what they see, without any editorializing or offering of opinions.

- What is going on in this picture?

- What do you see that makes you say that?

- What more can you find?

I never show anything from the traditional art canon as I learned it. I show something that becomes an addition into the new canon that I've been creating since I started teaching almost ten years ago: a canon of living, contemporary artists making work dealing directly with the issues of the times we are living in. Just like Nina Simone said we should be doing. That's my working definition of canon.

Usually I'll show an artist that I've bookmarked in my private feeds to come back to and investigate further later. The first day of class is a great excuse for me to learn something quickly enough to be a micro-authority. Often these artists are contemporary, marginalized in one or multiple ways by society and/or the art world, and—risky as it is to say it in these anti-DEI times—Not White. Not forever, not for all time, but not on the first day in my class.

I change it up for each class every semester, so no class gets a first day image twice, and nothing is repeated. It's a way for me to keep things fresh for myself, for me to learn something new on the fly, and for me to get my head in the game for a new 16-week semester. This January, I was teaching myself about the vast and shrewdly curious work and mind of Howardena Pindell. She is someone that I had never heard of until my 40s, and once I did, had much the same feeling as when I first picked up James Baldwin in my 30s. Why had no one introduced me to this person before?! Why was I never assigned reading, or shown a single artwork by this artist? Why am I just encountering them more than halfway through my life?

Howardena is a force.

And her artistic output has been so gloriously and greedily varied that there were enough disparate media and genres for me to show two different works of hers in two different classes that I'm teaching this semester.

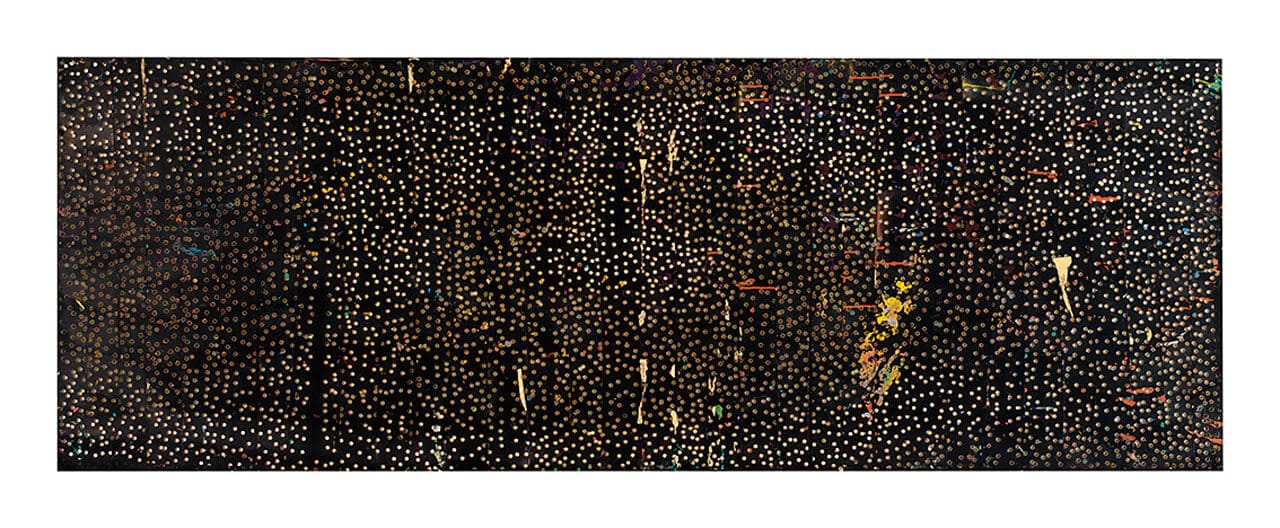

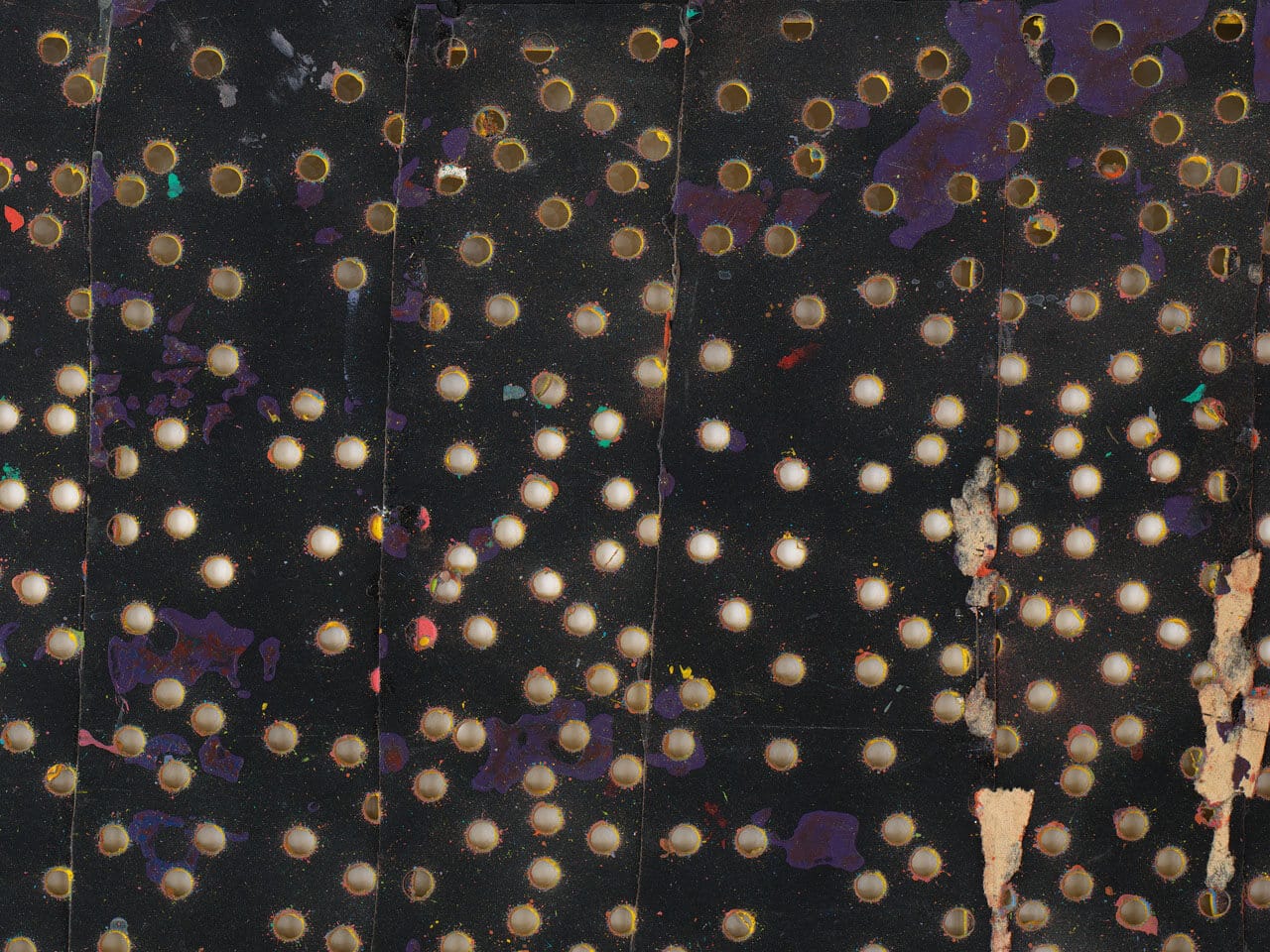

I never provide any context at first. Not the name of the piece, the medium, the name of the artist. I show the image and ask them to tell me what they see. In Introduction to 2D Design, the observations ran from obvious to lyrical.

I see dots and lines.

It looks like constellations of stars.

It looks like what I'd see under a microscope.

I see black vertical lines running in between the dots.

I see splotches sprinkled throughout the composition.

"O.K. You've been looking at the full view of a large work. Let me show you a detail of it and see if that changes anything for you."

A collective "Ohhhhh" fills the room, then quiet contemplation.

"I didn't see the purple before."

"There's a halo around the dots."

"The vertical lines now look like torn strips of paper."

"The dots are gold!"

"This is a really different experience up close than at full view."

After a few more opportunities for close-looking, I queue up a video of Pindell speaking about her work.

My name is Howardena Pindell. They obviously wanted a boy named Howard, so they stuck E-N-A at the end of it. I don't know of any other Howardena on the planet. I just say I'm an artist.

Then the moment of revelation. When the previously alienating abstract art becomes weighted with meaning and empathy.

I became very enamored of the circle. The circle came from an experience when I was a child during segregation. We visited my mother's mother and her sisters in Ohio. And my father loves root beer. So when the sisters were hanging out with each other we would drive to Kentucky, and we got chilled root beer in a glass, but on the bottom of our glasses was a red circle. That meant that it was for black people. You couldn't share any silverware or glassware with whites. That's when I think the circle really hit me, it became something that I wanted to undo in a way, or to express it in a way where the circle is beautiful and not used as a form of punishment, that you cannot drink from the same mug. What we now call "dotitis," the compulsion to cut or punch out circles—that started as a result of that red circle.

You can literally feel the shift in the room once the context is provided. People's body language relaxes, hard metal stools as chairs in the studio room notwithstanding. There is nodding, recognition and understanding. And, I'd like to think, a warming tenderness toward both Pindell the person and the art she has made that they have now been made aware of.

And then the class is "warmed up," receptive and awake to whatever comes next. Which is usually the course introduction and syllabi. If I start with that, it's boringly business as usual and they haven't bought into anything I have to offer yet. So much of teaching is about establishing a buy-in sense of agreement between educator and students. I promise this experience if you promise me your intelligence and participation. These first day image exercises are excellent first tokens of buying in.

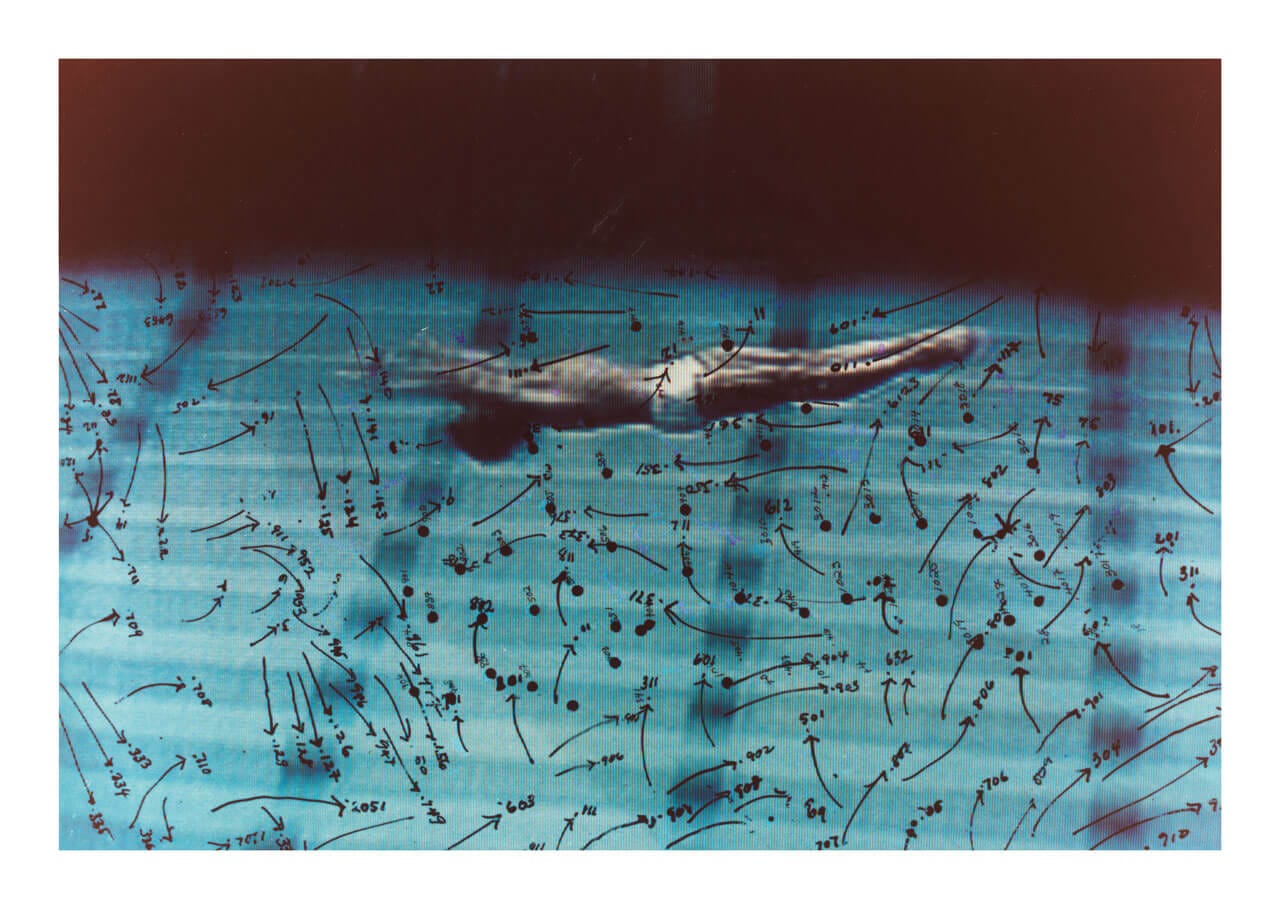

I teach two studio courses that day, and in the afternoon for Introduction to Photography, I show Pindell again to a roomful of new faces. Shown again, but differently.

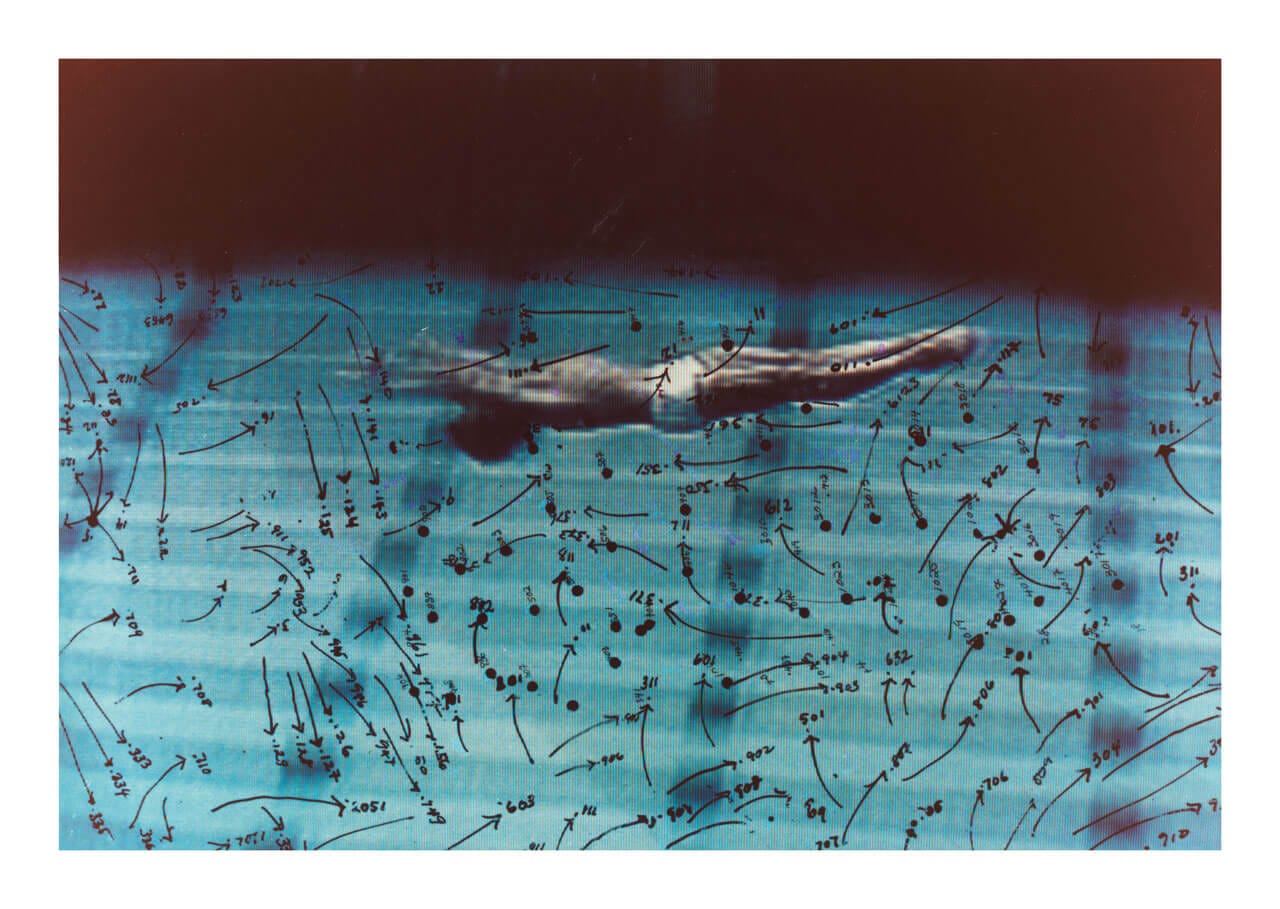

I see lines with arrows.

I see points with the arrows.

I see numbers written where the arrows are pointing.

I see a man mid-dive into a pool.

I see white banding in the image, like a bad print or...a flickering T.V.?

There's a big black something cutting off the top of the frame. What is that?

Maybe it's the top of the T.V.

Oh! You're right.

I showed the same White Cube video as in 2D, but I needed to do a little more work to make this image relevant to the content of this course. They'd already seen her work with the circles from the video, which provided me a segueway to talk about the genesis of the video drawings.

To rest her eyes from the meticulousness of the work with circles, her eye doctor advised her to get a television set for her studio. The irony of someone telling another person that the remedy for resting your eyes is to stare at a bright screen is not lost on me, or my class. This was the 70s, I say. As she began to watch during her mandated "rest" times, Pindell became interested in the cultural codes and signs visible in the programming that she was consuming. News, sports, popular television shows like "Flash Gordon" and classic films such as "Metropolis," were all fodder for a new form of work. Prior to this, Pindell had been drawing vectors and numbers on acetate. She placed these on top of the television screen, the static electricity adhering the acetate to it. Watching the t.v. in this new way, she would use a cable release attached to a camera to select moments that she thought made a good visual between the two media. Writing in Bomb magazine, Olivia Gauthier notes that:

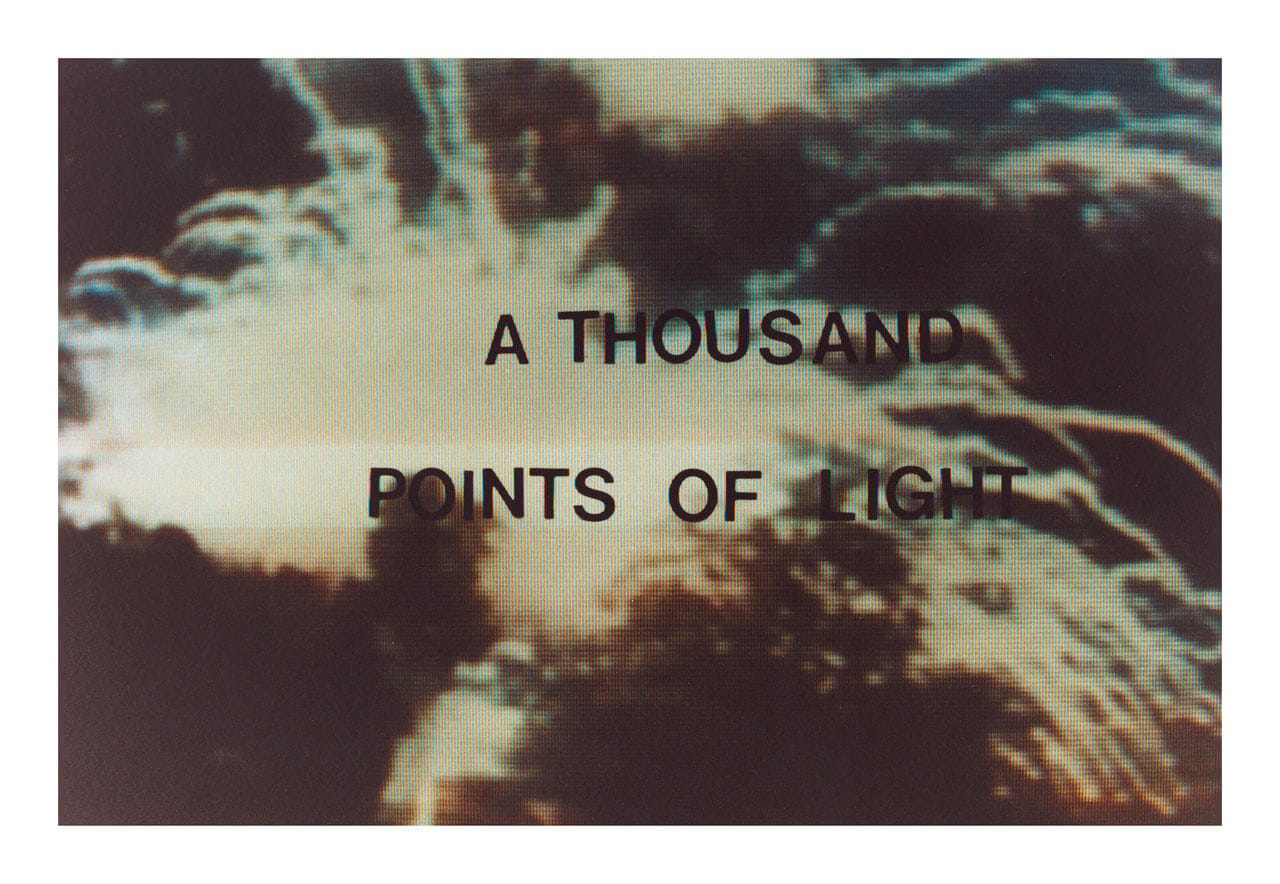

In her Video Drawings, Pindell calls more direct attention to the complexities of technology as related to social and political conflict, subverting the ideal of television as a democratizing force...The Video Drawings are one of Pindell’s methods of visually deconstructing information. Though it is now blatantly clear that television is not neutral, when Pindell began making these works, there was still a general optimism about television and its potential as a populist technology. Through her aesthetic investigation of the medium, Pindell solicits the viewer to look critically at mass media, and she warns against accepting the homogenizing aspects of television programming.

At first working with primarily sports imagery from baseball, hockey and swimming, Pindell later introduced text into the Video Drawings, combining them with stills from contemporary news reels, inserting her commentary on the Vietnam War, the invasion of Kuwait, climate change and Hurricane Katrina. In freeze-framing these images with the overlay of text and intuitive drawing, Pindell recontextualizes the televisual and its role in our lives, pointing out that medium's message is not always what it presupposes itself to be saying.

I view my role as an educator as one of the primary forms of resistance that I can practice every day and with the greatest amount of reach and impact. I know absolutely that students being able to see themselves in artists that look like them, share some of the same concerns that they have, or have had similar life experiences makes art real, and empowers seeing themselves as participants in the art world as tangible. Explaining the "why" of literature, criticism, art-making and more is the antidote to the untrue and vastly generic assumption that "art doesn't do anything" or that "art doesn't matter." It is a privilege and very educational for me to have a direct line to young people's thinking and understanding of themselves in the world at this moment. It's my sense that lots of folks my age only encounter the demographic that I interact with daily as parents or in a professional and detached setting. Once my students have "bought in" to the fact that I am as equally invested in them as they are willing to invest in their own education, I am granted entry to their worlds in a way that others who are not their peers never will be.

In the conversations about getting rid of DEI, generations of people who have come of age learning that different does not equal dangerous, that sexuality can be a tapestry, that coming into frequent contact with those from different places and spaces can expand one's understanding of themselves, the world, and their place in it—these same folks are now being tossed into a maelstrom of white-washing and erasure. Myself and other peer educators have been paying close attention to the language of upper administration, noticing both what is and is not said. In a recent letter to the whole University system, the President struck a tone that will be reminiscent to anyone familiar with the backlash against those in the BLM movement:

"We are dedicated to all of Colorado’s communities, not just some of them." (emphasis mine)

In particular what I've noticed campus-wide (and in the President's letter above) is a removal of any language acknowledging or supporting LGBTQIA students whatsoever. Over the past five years, the number of trans students that I have enrolled in my courses has tripled, to the point where I have multiple students identifying as trans in every class that I teach. They are not going to disappear or shrink away just because official communications stop acknowledging or supporting them. Nor should they.

I will not pre-emptively acquiesce. I am not going to pre-obey anything. Growing up evangelical (and abandoning it at twelve), I hate hate hate that word. Since when did the public university become a religious purity test? The world of higher education may be looking or becoming different, but it is my hope that my colleagues and peers do not do anything differently except double-down on their freedoms and their responsibilities to those that they teach.