A drowsy, dreamy influence seems to hang over the land, and to pervade the very atmosphere...the place still continues under the sway of some witching power, that holds a spell over the minds of good people, causing them to walk in a continual reverie. They are given to all kinds of marvellous beliefs; are subject to trances and visions; and frequently see strange sights, and hear music and voices in the air. —The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, by Washington Irving, ca. 1819

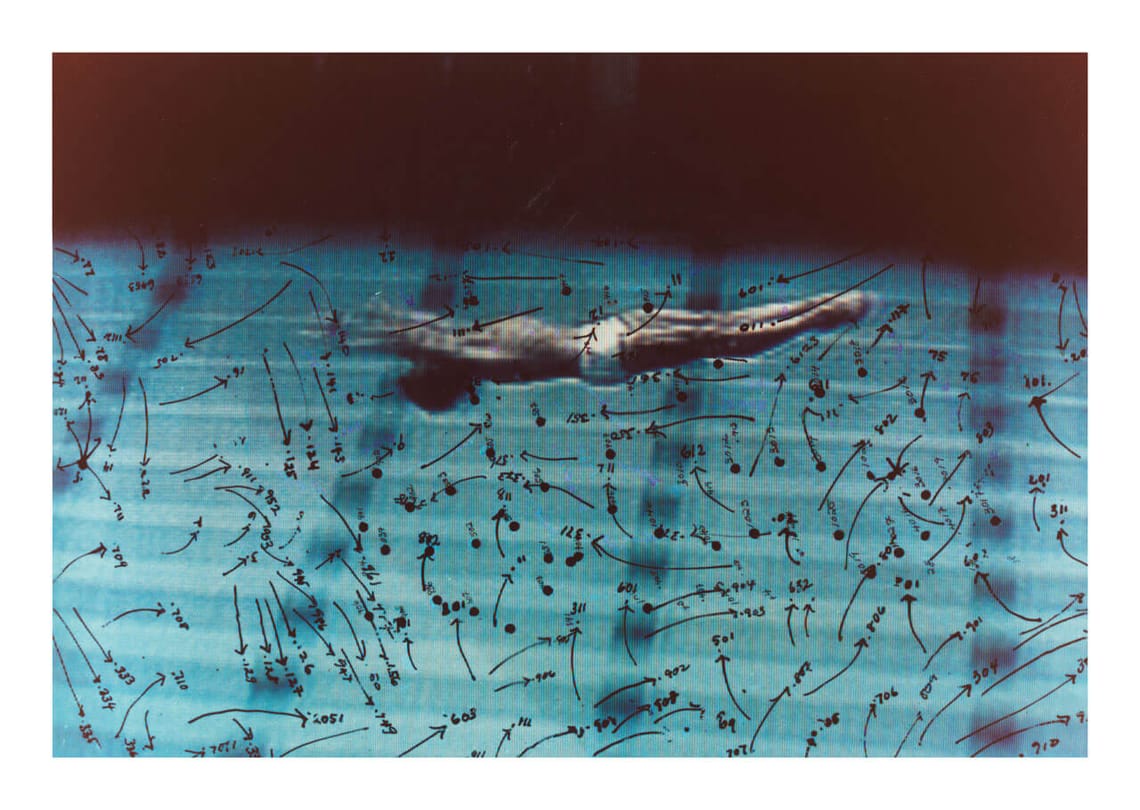

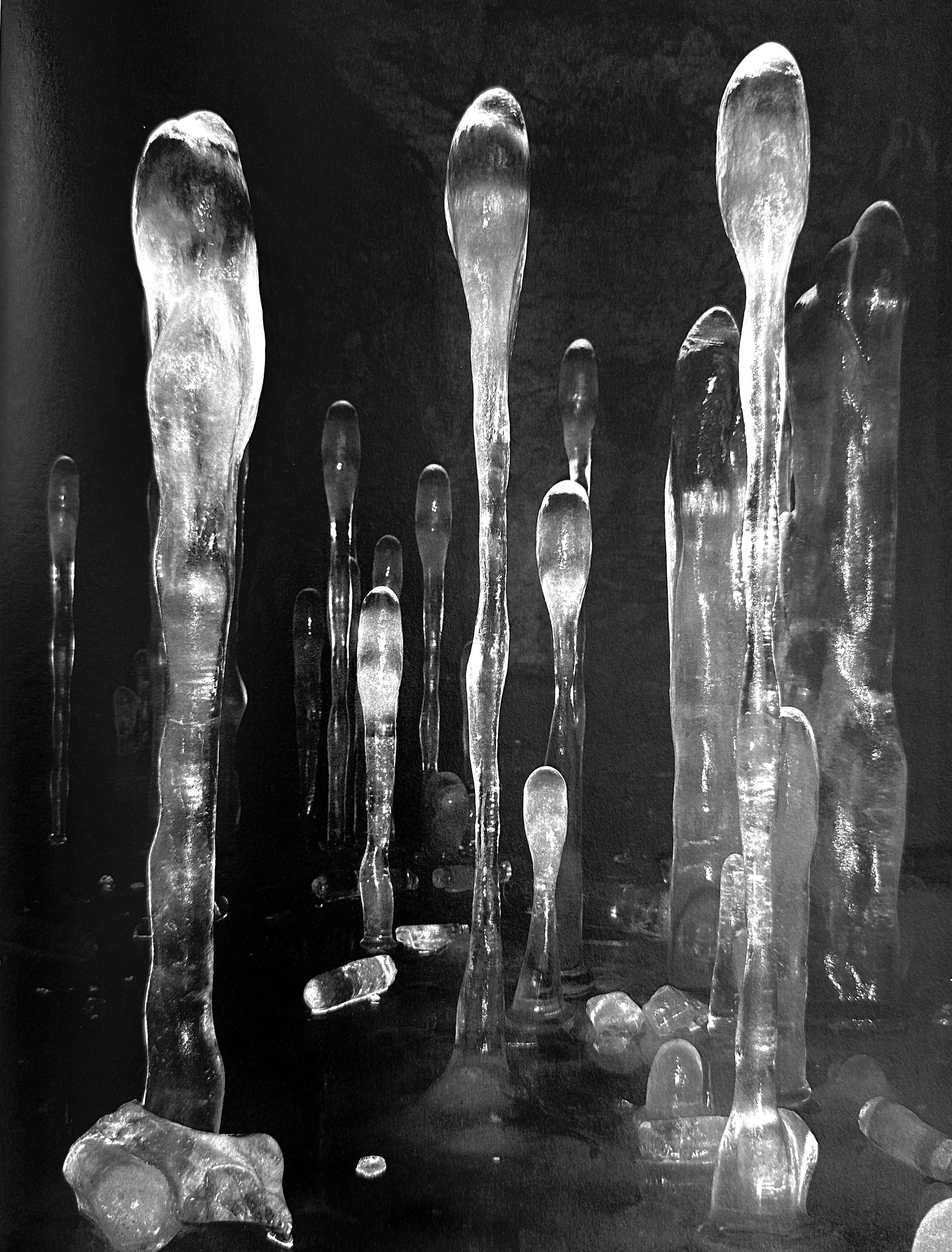

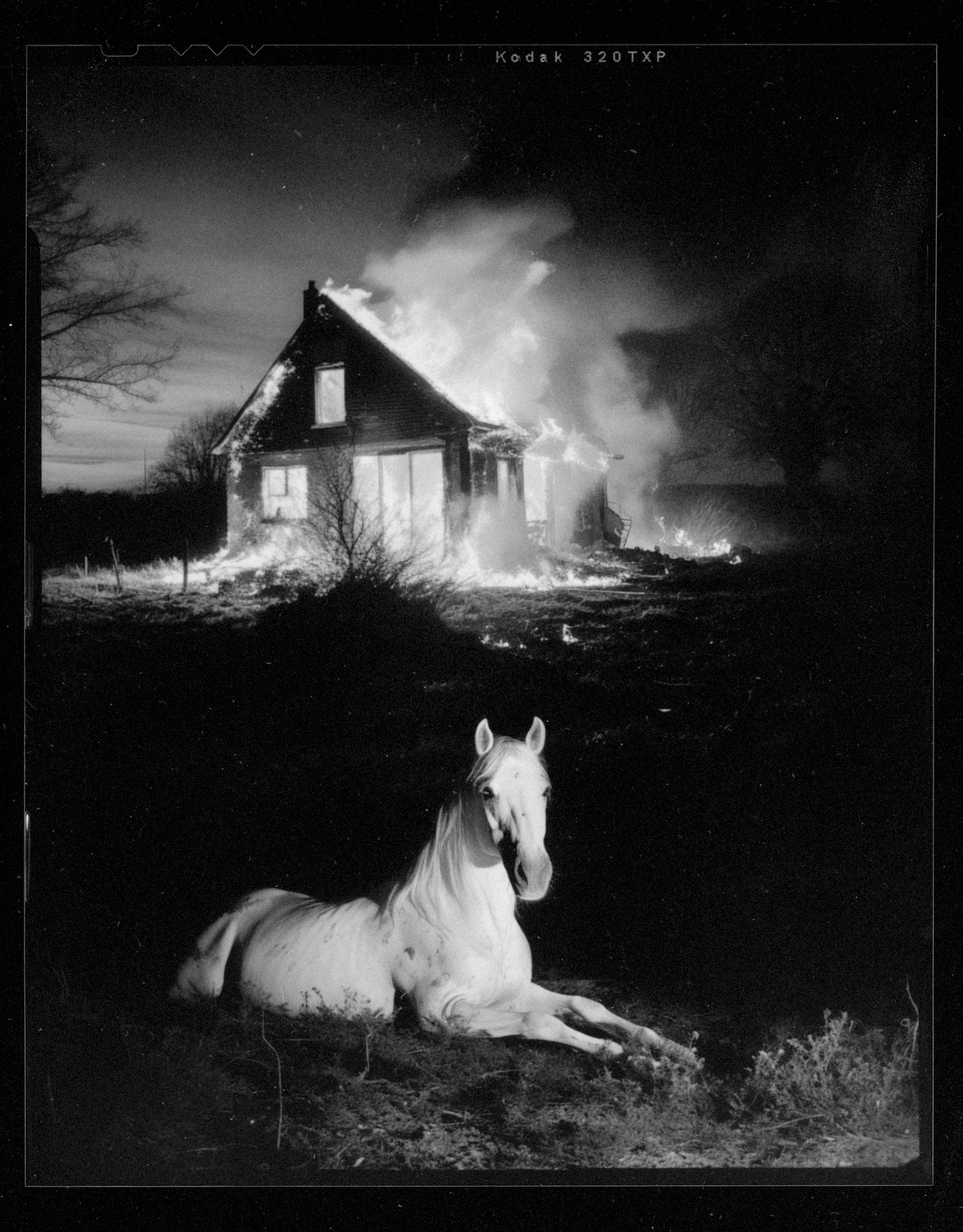

If the photographs from the collaborative photobook Sleep Creek, by Dylan Hausthor and Pia-Paulina Guilmoth, had a scent, it would be that of decay. Something burning somewhere not-so-far-off that I would dread knowing the source of, fearing it to be either unnatural or its opposite: all-too-natural. The book contains metronomic and varied repetitions of bats, entrances, incantations, emissions, things on fire, waxy death, spider work, tangled things—and all of it mixed with a suggestive whiff of medieval peasantry. The place depicted in Sleep Creek is not one that I wish to live in or visit; but were I to encounter it I would never stop thinking of it. As a sequence of supernatural visuals, I can't recommend it highly enough.

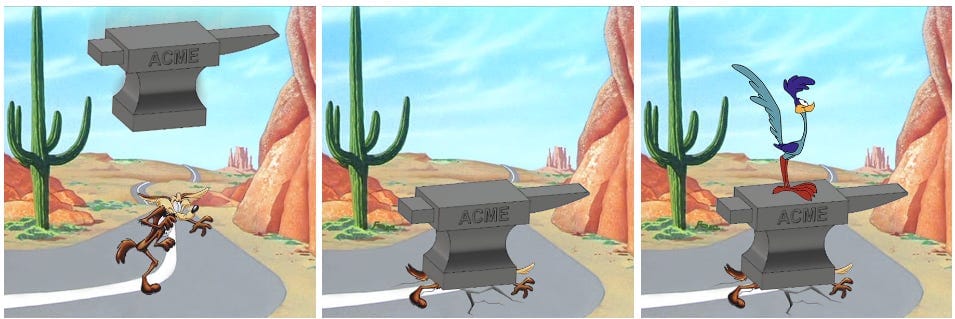

The allusion to Washington Irving's famous short story The Legend of Sleepy Hollow is apt, because the land of Sleep Creek is a modern-day version of the "land of the fairies" chronicled in folklore, myth and Arthurian sagas. As photobookstore noted in their blurb of the book, Sleep Creek is a place where "There are no beginnings, middles, or ends in their experiences of the world, nor a hard line between the experienced and the directed." Like all good stories, there are elements of "truthiness" mixed with fictive yarn-spinning—all in the service of getting at something that looks like the experience felt. A harder truth to conjure, resulting in, as Brad Zellar notes in his on-point review, "a disorientation that works."

Sleep Creek was shot entirely on one of the 4600 islands off of the coast of Maine; in Hausthor and Guilmoth's 2024 separate solo publications (What the Rain Might Bring, and Flowers Drink the River, respectively) the stage resets and reorients for the two artists, who are using similar ingredients, but working on entirely different recipes.

l—r: Dylan Hausthor, What the Rain Might Bring, tbw books 2024; Pia-Paulina Guilmoth, We Make A Flower, Flowers Drink the River, Stanley/Barker, 2024.

Same: hands, flowers, spider webs. Different: Hausthor's flowers (dahlias?) are sturdier and more visually striking than the daisies pictured in Guilmoth's image; the hands in Hausthor's photograph drip with a viscous ooze that could be anything from flower sap, to elmer's glue, to amniotic fluid. In Guilmoth's image, the spider web glitters jewel-like with mica dust, and the acrylic nails on the hands of each participant engaged in holding/displaying the web echo in a cheerful refrain of glitter and glimmer. One beckons with the inevitable stickiness and sometimes toxic/sometimes harmless residue of life, the other entices with a kind of prettiness that attracts both mates and prey (that are sometimes one in the same). Hausthor's a rite of passage; Guilmoth's a secret spell.

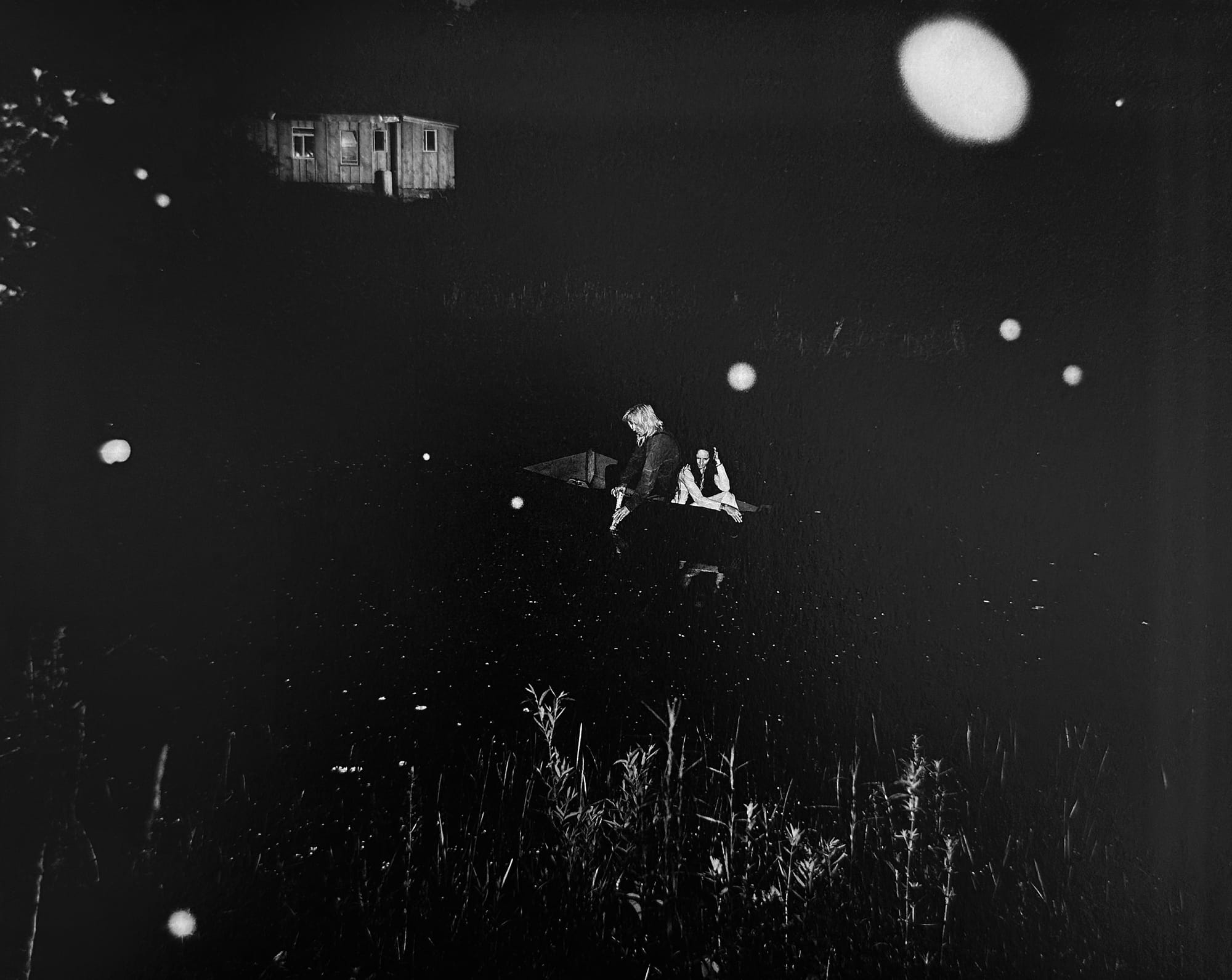

l—r: Dylan Hausthor, What the Rain Might Bring, tbw books 2024; Pia-Paulina Guilmoth, a. & o. (bass pond), Flowers Drink the River, Stanley/Barker, 2024

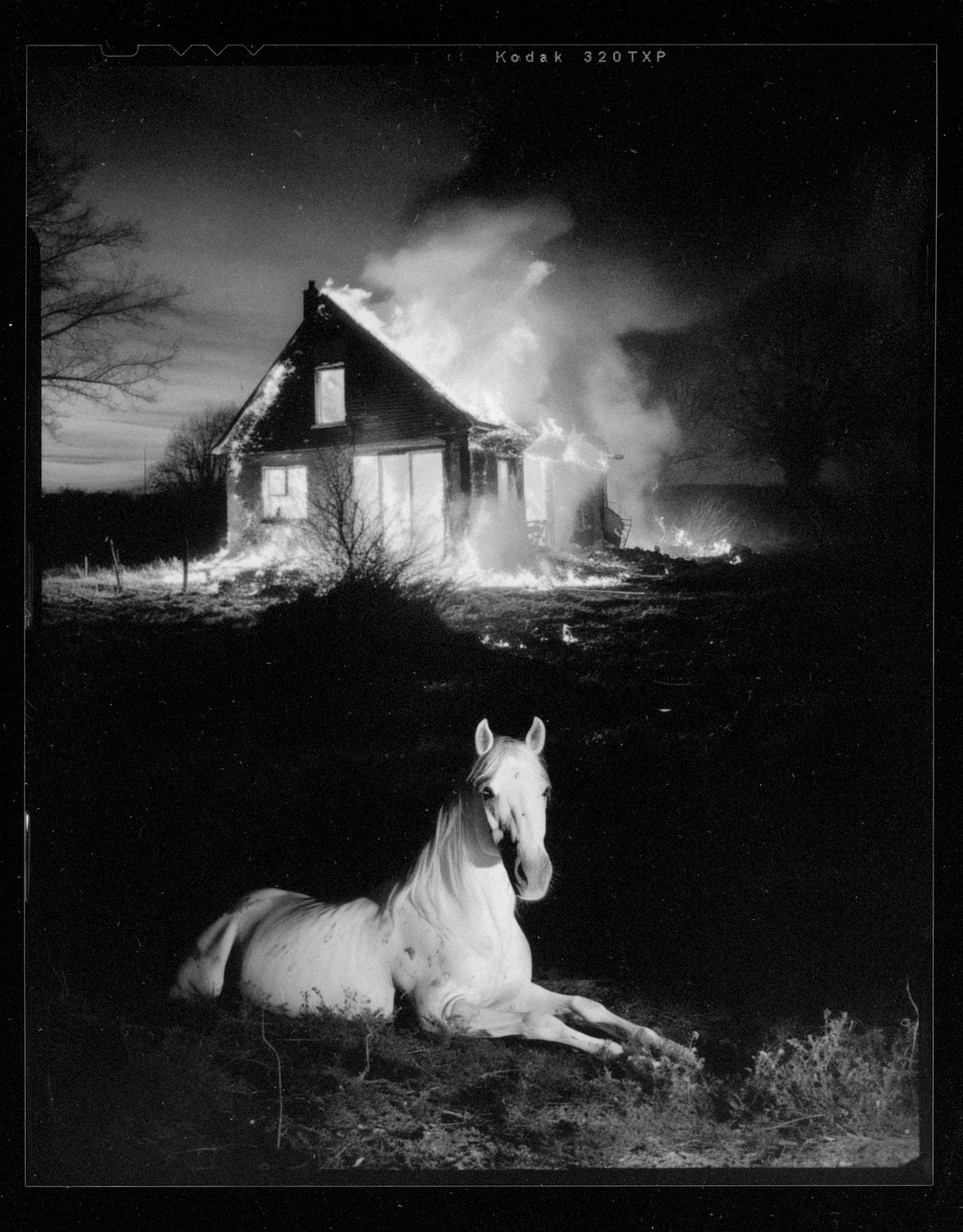

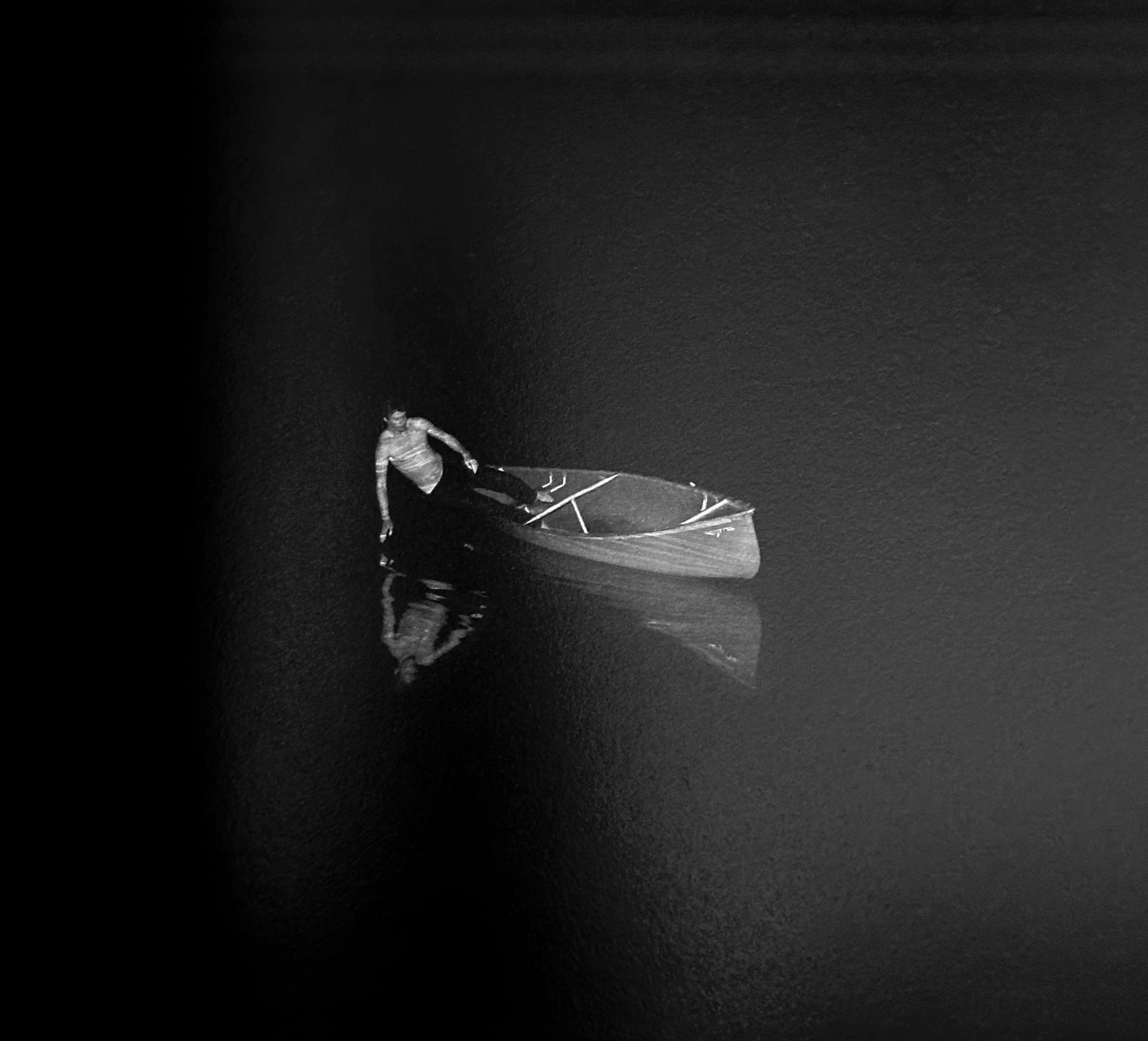

Same: boat, figure(s), water, night. Different: Hausthor's figure tips ominously from the boat, hand skimming the water and their image reflected in the mirrored black liquid. There's no way he doesn't fall in. Is he drunk? Asleep? Inviting death? Our decanted hero and the vast expanse of dark water fill the frame, tipping us with him. Will the cold water wake us up or shock our body into drowning? Why did we go out into that dark bay alone and half naked?

There are more elements to consider in Guilmoth's photograph: rain or snow or lightning bugs dot the foreground, a partially lit structure sits on the shore behind the two people in the boat. Instead of the glassy even surface of water in Hausthor's image, here is thickness and bugs, grasses and mud. I hear a night chorus in this image: crickets, bullfrogs, nocturnal raptors and motion in the brush of reeds. Quiet conversation in the boat; the sound of the paddle in the dense pond. What feels different with two in the john boat as opposed to a solo sojourn in a canoe? Company, intimacy, quiet. The proximity of the house in the background suggests a return and a nearness to hearth. Is this for pleasure or sustenance? Does one go fishing at night?

Hausthor's subject courts danger; Guilmoth's people speak a quiet calm.

l—r: Dylan Hausthor, What the Rain Might Bring, tbw books 2024; Pia-Paulina Guilmoth, Rhubarb Mother, Flowers Drink the River, Stanley/Barker, 2024.

New England is a place of witches and spells, ghost stories and legends, secret knowledge and gossip, strangers who are friends and neighbors who are strangers. Both images are interiors: Hausthor's dolls are strung in a barn, hanging in twisting repetition against a backdrop of stacked hay. Harshly lit, their shadows loom twice as large on the bales. Clothesline zig-zags up and down, back and forth through the frame, faceless and featureless mummy dolls turned towards us, away from us, facing one another. A single one prone on the floor, feeling like it failed a test. Am I wrong for thinking I've just stumbled into a scene from the X-files? It feels like I might be led to a hidden cellar where a coven is chanting in a language I can't understand. Or that someone just outside the frame has just retrieved a permanent ink pen, ready to name and mark each of the dolls. The photo feels loaded and spare at the same time.

Guilmoth's rhubarb leaves all have spooky faces punched out by nature or by hand, a grid of ghost faces, unity in variety, looking out at us in their separate states of surprise and dryness. Here, the clothesline is neat and consistently, evenly strung. Use feels more culinary or pharmacologic as opposed to dark arts. As in other comparisons, there is more to look at in Guilmoth's image, and the more here creates more questions as well as alters my mood. The small oriental rug tells me I am in a living space, as does the fluffy, non-barn yard-looking feline in the right corner. A bare bicep and elbow peep out questioningly from the corner, and just when I think I've taken in everything, I notice the face peeking out of the eyeholes in a central leaf, then blonde hair and coat and legs. Is that a mirror? And a face looking back at me in the mirror! And more still—a class portrait of girls standing in uniforms suddenly announces itself as hiding in plain sight. Guilmoth's photo is a confusing, crowded jumble that amuses me the more that I look at it, gently mocking me for ever having been scared or startled.

l—r: Dylan Hausthor, What the Rain Might Bring, tbw books 2024; Pia-Paulina Guilmoth, Sister Spits River Water, Flowers Drink the River, Stanley/Barker, 2024.

People hunched over, spitting into the grass. Hausthor's person has a mud-covered head and face, steadying themselves perpendicular to the earth. The spit-trail starts from their body and tethers them to the ground. Why is the head covered in muck but not the white shirt? Is this a punishment, an initiation, or some odd form of self-care? We are visually close in here, the supporting arm creating a strong weighted diagonal, anchoring us into the tight space with the muddied person. The grass is thick and coarse, the kind you dream of laying in barefoot during summer. Their eyes are closed and when they open, the grit will irritate and close them again. Does the mud smell like fresh earth or like putrescence? Are they steadying themselves in relation to the ground or about to fall into it? It is night, always night, in Hausthor's pictures. Not always so in Guilmoth's.

Sister Spits River Water is instructive: don't drink the water, you might get sick. It's daylight, a soft breeze, the same dreamy grass to sit in, an older pair of feet and legs jutting into the side of the frame, letting us know that we are never alone in Guilmoth's world. Maybe sister was just swimming, and has recently donned an oversized t-shirt for warmth. Maybe it's a no-pants summer and this is just how it is most of the time. She's not looking at anything or anyone, but is not caught up in a dazed spell, it's just a moment in time, like photographs are wont to be. A moment of repose instead of one of recovery.

l—r: Dylan Hausthor, What the Rain Might Bring, tbw books 2024; Pia-Paulina Guilmoth, Matriarchy, Flowers Drink the River, Stanley/Barker, 2024.

I’m interested in storytelling and the extraordinary—dying, fucking, thriving, giving birth, love, caution, abandon, absurdity, touching, lying and laughing. The environment is nothing if not full of these things. —Dylan Hausthor

I resonate with artists that photograph their own communities that they belong to, and people that love and trust them... I try to make photographs that take the viewer to a different place that is unlike the one experienced in everyday life. Which i think is the goal for most rituals whether they are spiritual or religious or transcendent. —Pia-Paulina Guilmoth, in conversation with Alessia Glaviano

What the Rain Might Bring has a title that pays homage to David Arora's 1991 mushroom hunting guide All That the Rain Promises and More. The latter features a cover photo of the author that would be at home as a character in one of Hausthor's imaginings: a mischievously grinning fellow, disheveled, tuxedoed, crouched and holding a trumpet in his right hand and a gigantic chanterelle mushroom cluster in the other. Hausthor's book is carefully structured, and has visual pacing that's similar to that of a psychological thriller. If the title is an invitation to wonder, then the answers are given to us as more questions. The people are queer, in the 1740 sense of the word meaning "open to suspicion, doubtful as to honesty," and nature itself is queer, in the sense of the 15oo's word meaning "strange, peculiar, odd, eccentric." There are portents, signs, things that are pregnant with meaning and other things that don't mean anything other than what they are, and what they are is just fantastically there. I counted 18 spiderwebs that are either the subjects or intrinsic to the subject of the image among the 79 that populate the book. Of spiders and webs Hausthor notes that, "This creature has a sort of fraught ethical relationship to its consumption, as do I and photography."

Mennonite women and other arrangements appear in groups and disappear from the narrative, sometimes against a stark white background that is near blinding, at other times with raindrops on the camera lens, obscuring from our sight what we think we might be seeing. Mushrooms burst out of the earth like titans, taking up the space of the entire 4x5" frame, and us with it. A goat's neck slit and bleeding out into a bucket, with gentle hands holding the head; later a fattened goat, seated contentedly next to a man sprawled out amidst a nightmare of hoarding. Strange happenings are documented, hearkening our awareness to biblical scripture, plagues and meteorological phenomena.

What the Rain Might Bring, Dylan Hausthor, 2024.

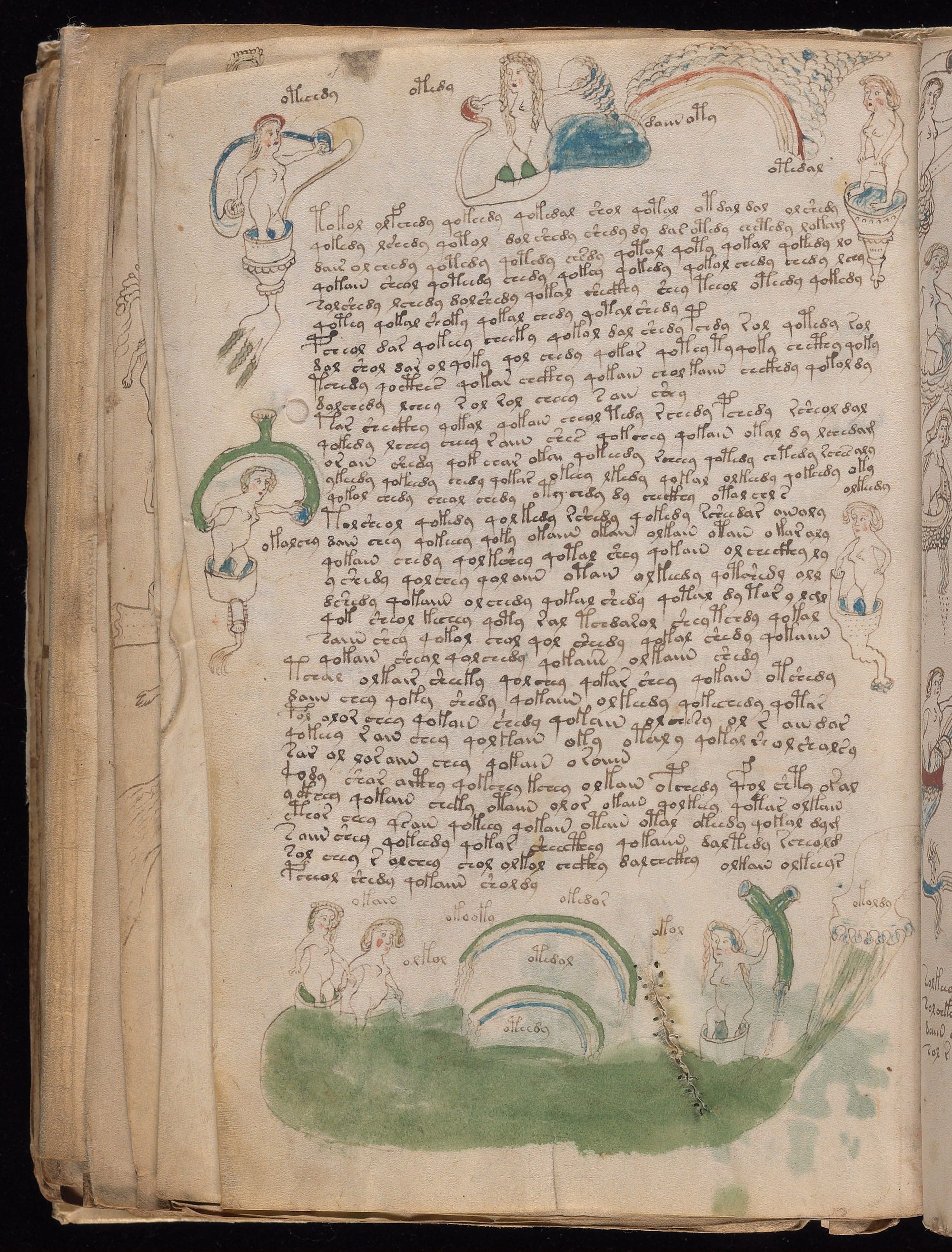

While there is no text in the book, the type of the title featured on the cover is itself significant. In an interview with Jake Benzinger of Lenscratch, Hausthor said:

The type we made was inspired by the famous Voynich manuscript. It’s a type modeled after a Voynich script, which is this deeply mysterious, questionably cracked manuscript that like the existence, or seems to argue the existence, of a lot of mythical realities… it’s so interesting and I’m sort of obsessed with it as a source of bookmaking inspiration.

The Voynich manuscript lives in the vaunted collections of Yale's Beinecke's Rare Books and Manuscript Library, and has a storied history of being either the world's most indecipherable cipher, or the world's most elaborate hoax of one. Rare mysteries and rarefied hoaxes sit well together in Hausthor's pantheon of possibilities, and understanding some of their imaginative fixations serves as an insightful and intuitive "in" to the psychic terrain of his image making.

As I finish a pass through the book and then start my way back through it again, the title and its possible variant meanings flash to the front of my mind. What the Rain Might Bring. What manner of rain? The destroying kind or the redemptive kind? And who or what is doing the bringing? Both answers right, valid and both answers wrong. Hausthor has made a confounding series of images meant to be experienced as a book, but not as a conventional story. It's a book of feeling, not fact. Harsh light and unreal darkness. Fucking and dying. It follows the lineage of Sleep Creek but is its own child.

If Hausthor's book requires referencing the origins of the word "queer," Pia-Paulina Guilmoth's Flowers Drink the River has its own watch word whose historical meaning appears throughout the book in a refrain, and benefits from further understanding.

glamour (n.)

1715, glamer, Scottish, "magic, enchantment" (especially in phrase to cast the glamour), a variant of Scottish gramarye "magic, enchantment, spell," said to be an alteration of English grammar (q.v.) in a specialized use of that word's medieval sense of "any sort of scholarship, especially occult learning."

OED: 1.a.1720–Enchantment, magic. Often in to cast the glamour over and variants: to put a spell on; to enchant, bewitch; (in extended use) to gain influence over (a person) by using one's charm.

1720

Like Belzie when he nicks a Witch..He..Casts o'er her Een his cheating Glamour.

A. Ramsay, Rise & Fall of Stocks 271 in Poems (ESTC T154560)

Guilmoth shares at the end of the book that she began medically transitioning during its creation. Flowers Drink the River is a two year photobook creation that parallels the first two years of Guilmoth's gender transition. In an interview with Photo Vogue, she said:

A common misperception is that hormones just alter your appearance, which couldn’t be further from real. Hormones began to change the interior landscape and brain functioning before anything else. It’s a mind/body harmony that is in a constant state of growth and discovery. I started working on Flowers Drink the River about a week before starting hormones. I had a sense of hopefulness and excitement in starting my life over again, which fueled me to want to create something beautiful and celebratory. I was also confronting the terrors of being a transsexual in a rural, mostly right-wing town. Making art is one of the ways I can find some solace.

If What the River Might Bring feels like dread in places, Flowers Drink the River feels generative. As with Sleep Creek, Guilmoth is photographing in a similar place—still rural Maine—but it's in a different spiritual zip code. There are woods, caves, mud and so, so many spiderwebs; words like fecundity, care, bedazzlement, elemental, ritual and glamour—in the magical sense—occur to me. I don't feel dread in these images, as I often do with Hausthor's work. But I don't feel the opposite of dread, either. It's more like the music is different. Different eyes are looking here, and different eyes are looking back.

In Guilmoth's imagining, the mists of the land of magical beings have parted and we're given a view into a secreted world that resides in resistance to culture and place, where there is impossible beauty and impossible-to-comprehend terror; there is also community, adaptation, stages of life and becoming.

Resistance for me is saying: “you can try and take everything from me...but you can’t take away my joy and the ability to find beauty in my life”. Trans people, amongst other marginalized communities, have so many threats to our merely existing in this world.

For me it’s really important to photograph the people and things that I have real relationships with and care about. —Pia-Paulina Guilmoth, in conversation with Alessia Glaviano

Many images are still taken under cover of night, flash still illuminates humans, spider silk, snakes, deer and barn owls, but there is a gracious amount of daylight as well. Guilmoth has spoken of the night being a reprieve for her and the daylight was something to fear—as a transgender person living in a red, right-wing, conservative rural place. Taken as a whole in Flowers Drink the River, my sense is that she has made a tentative peace with the daylight, as the flow of images are not in tension with one another, but reconciled. If hope exists here, it exists in the spaces where expansiveness is on view: the night sky illuminated by stars, a pond shot at a slow shutter speed during some natural light that reads as revelatory.

Turning the pages of What the Rain Might Bring is akin to an occult initiation. Spending time with Flowers Drink the River is like being invited to dance naked in the woods with the coven under a full moon. Both have their charms.